|

Old Stuff from the Oil Fields

Water from the surrounding rock formations typically flows into the hole during drilling, but if no water is present, then it needs to added so that the pulverized drilling debris, which are known as cuttings, can be converted into a thick, muddy mess. As more and more cuttings accumulate, they eventually need to be removed in order for drilling to continue. To remove the muddy cuttings, the bit is pulled out of the hole, and a "bailer" lowered down in its place. The bailer is really nothing more than a piece of pipe with a dart valve on the underside. When the dart touches the bottom of the hole, it pushes up and opens the bailer so that mud and cuttings can flow inside. The dart closes when the bailer is raised, thus trapping the cuttings, which are emptied into a pit next to the derrick after the bailer is hauled back to the surface.

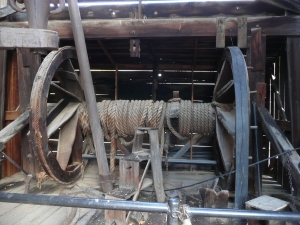

Spring poles were ultimately replaced by steam engines that powered a walking beam on a samspon post, which would in turn lift and and drop a cable and bit suspended from a derrick. When the bit was out of the hole, a derrick also made it easier to drag up a bailer full of mud and cuttings. The spring pole below is compared to an engine and derrick. If the well was a success, then the sampson post and walking beam, shown in yellow to the left of the derrick, could be converted to a pump jack to produce the well.

The early alternative to the cable tool was the hand auger, which when mounted on a tripod as shown below, could drill a shallow hole. The problem of course with an auger was that pipe had to be added to the tool to extend it as the hole got deeper, which meant the auger got heavier and heavier as the well went down.

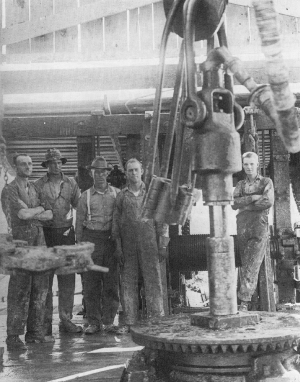

Though it took time, rotary drilling slowly made slow inroads in the oil patch, and today virtually all wells are drilled with rotary power. A picture of a drill crew on an early rotary rig at Coalinga field in 1917 is shown below. They are standing in front of the "kelly bushing", which is a device that clamps around the "drill pipe" and rotates. Because the drill bit is screwed onto the down-hole end of the pipe, as the kelly bushing rotates, the pipe rotates, and with it the bit to make hole. The "drilling fluid", also called "drilling mud", is a muddy mixture of water and additives that is pumped down through the drill pipe and out through the bit. As the drilling fluid flows around the bit, it picks up drill cuttings and carries them to the surface by traveling upward though the "annulus", which is the space between the drill pipe and the walls of the hole. Because the drill cuttings are brought to the surface with the mud, this eliminates the need for a bailer.

|

|

The obvious next step was to use an engine to drive the auger, which gave rise to rotary tools and the "rotary bit", an example of which is shown on the left. The first rotary rig in California arrived at Coalinga field in 1902, but drilled a hole so crooked that a cable tool rig had be brought in to redrill the well. This naturally gave rotary tools a bad name in the California oil fields. Nontheless rotary drilling rigs and crews arrived in California from Louisiana in 1908 and successfully drilled wells at Midway-Sunset field that erased the embarressment of the Coalinga experiment six years earlier.

The obvious next step was to use an engine to drive the auger, which gave rise to rotary tools and the "rotary bit", an example of which is shown on the left. The first rotary rig in California arrived at Coalinga field in 1902, but drilled a hole so crooked that a cable tool rig had be brought in to redrill the well. This naturally gave rotary tools a bad name in the California oil fields. Nontheless rotary drilling rigs and crews arrived in California from Louisiana in 1908 and successfully drilled wells at Midway-Sunset field that erased the embarressment of the Coalinga experiment six years earlier.